I thought it could not be done. I could not even imagine what it would be like. Did I have the courage to make it through the entire quest? This was one of the most difficult decisions I have made during my time in Italy. I consulted my classmates and asked them if they were willing to join me. Many refused immediately and looked at me as if I were crazy. Some even tried to dissuade me, telling me that it was an insane idea and I would regret it later. I ultimately decided to be impulsive and I accepted the Great Gelato Challenge.

From the first day that I arrived in Italy, I have been a gelato enthusiast. I had my first taste when I ordered a cone of nocciola gelato from a minuscule gelateria in the Campo de’ Fiori. The creamy, cool taste of hazelnut was unlike anything I had ever tasted. This ice cream actually tasted like the flavor it advertised! When I saw a toddler walking past me with a cone of gelato that was almost as big as her head, I knew gelato would be a significant part of my Italian experience. Weeks later, I would joke with friends about going to gelaterias and ordering every flavor they offered or buying gelato by the kilo to eat in one sitting. Despite all of my grandiose plans, I always knew that I would not and probably could not ever eat that much gelato. On the night of the Great Gelato Challenge, I tested all of my gelato-eating limits.

The idea for the Great Gelato Challenge originated from a debate over which gelateria should be deemed best gelateria in Florence. There were the staunch supporters of Grom, who claimed that the sophisticated flavors at this hangout, favored by the locals, distinguished this gelateria. Others insisted that Perche No?, with its neon lights and friendly servers, was by far the superior gelateria because it offered a lively atmosphere along with reasonably priced gelato. On our second trip, Vivoli attracted a new following with its refreshingly realistic fruit flavors. After listening to the increasingly heated debate, four of us decided that we would try gelato from each of the gelaterias to decide, once and for all, which gelateria is the best in Florence.

Kelsea, Joel, Gabrielle and I (the Great Gelato Eaters?) started at Vivoli, where we were joined by the rest of the group. We decided then that we should probably play it safe and only order small servings, at least to start. Excited by my mission, I ordered a small serving of pistachio and dolce di latte gelato. This was clearly my first mistake of the night. The strong nutty flavor of the green pistachio and the sharp sweetness of the dolce di latte clashed when swirled together, but this did not deter me from continuing my quest. The gelato, perhaps because it had been sitting out all day, was more like semi-freddo and felt like slush in my mouth. I was not a fan. I quickly finished my cup of gelato (I was going to eat six flavors of gelato, there was no room for cones) and we headed off in the direction of Perche No?

We turned onto via Tavolini and easily spotted the familiar gelateria because it was the only building on the small street that glowed with neon lights. We slipped in as three tourists left and quickly surveyed their selection of flavors. I was disappointed to see that they no longer had one of my favorite flavors, green tea, so I settled for cinnamon and albicocca, which was an unusual combination that I had not tried before. The cinnamon tasted sweet and warm while the albicocca had a fresh, slightly tart taste. This became one of my favorite combinations, but my momentary happiness was interrupted by groans from Gabrielle when she realized that her misunderstanding with the server resulted in what is now known as the Great Gelato Mistake. She thought that panna montata was a type of gelato, while it was actually just regular panna. This resulted in her having a cup full of cinnamon gelato with whipped cream on top, which was too much spice by itself. I looked at my watch and realized that it was getting late, so we decided to eat the gelato on the way to our last stop, Grom.

Unfortunately, we reached Grom in less time than I anticipated. In fact, I still had not eaten most of our gelato from Perche No? I experienced my first pangs of gelato guilt as I realized that I had become a chain gelato eater: I would be discarding the cup from one gelateria while ordering gelato at another gelateria. Gabrielle and I darted behind the cover of a nearby building, too embarrassed to stand in front of Grom as we ate our gelato. I inhaled the small serving of gelato, with help from Joel and Kelsea, and we walked into Grom. I became disoriented as I walked in from the dark night into the brightly lit gelateria. At this stage in the Challenge, Joel and Kelsea dropped out, citing feelings of “fullness” as their downfall. It was up to Gabrielle and me to finish the quest. We decided that fruit flavors would probably be the lightest and the easiest to stomach at this point. I ordered the classic combination of limone and lampone. I sat down on one of the wooden benches inside the crowded gelateria and halfheartedly began to eat the gelato. The sour limone and the tart, crisp lampone matched well together, but I could not enjoy the flavor as I was suffering from gelato fatigue. This is the last one, I told myself with each bite. We ate in silence, not wanting to admit that we did not want to see another cup of our beloved gelato for at least a few days.

As we walked back to our hotel, I experienced a strange feeling of pride mixed with nausea. I did something impulsive and crazy! How many people can say that they went on a gelato marathon in Florence? I crawled into bed that night feeling sick, but smiling because, by finishing the Challenge, I could officially call myself a Great Gelato Champion!

Saturday, October 27, 2007

Creative Writing #8

We walk quickly through the last few exhibits on the way to the exit. The modern paintings we pass are a blur of color on a black background as I rush past them in a hurry to leave and meet the rest of the group outside. All of them have the same theme: bright background with splashes of color that showed people and objects in supposedly natural scenes. I glance up between long strides to catch glimpses of these paintings that I have not seen before. Man on a horse. Women wearing flowing dresses. I know that if they are displayed in the Uffizi, they are probably significant works by important painters, but I do not have time to appreciate them for their artistry. I look back to see three other students hurrying past all of the paintings, almost sidestepping through the gallery so that they can quickly absorb all of the art that surrounds them. One more exhibit. One more room. Red “uscita” signs propel me forward through the museum. I pass through a small display of paintings and barely pause to look up. When I see it, I stop immediately. I step closer and almost laugh out loud.

I have stumbled upon a Caravaggio! Bacchus, with his glass of wine and headdress of leaves, looks up at me from the tiny canvas. I was drawn to this small painting on a small table because of the dark background that contrasts with all of the bright paintings around it. The main figure, a young man dressed in a white toga, is posing for a portrait. He is fair-skinned, but his cheeks and face are flushed, probably the result of his indulgence in the wine that he is holding. A bounty of fruits is placed on the table in front of him and he wears a headdress of leaves. His left hand lightly grips a large glass of red wine as he reclines slightly to his right. His youthful face shows no sign of distress or unhappiness. I look around the room and I am surprised to see another Caravaggio painting, this time with Medusa as his subject, on display behind me. I quickly scan this image, trying to record it in my memory, before turning back to Bacchus. I am most interested in how much he resembles a real human boy. He is a beautiful boy, but he does not have the idealized, mature face that I expect from an artist portraying a god. After my limited viewing of the painting, I conclude that the painting is a portrait of the god Bacchus who is enjoying himself, as usual, by partaking of wine and a bountiful selection of fruits.

My surprise at finding a Caravaggio has inspired me to learn more about this particular painting. Scholars have hailed this piece as a prime example of Caravaggio’s developing talent with realism. His Bacchus does not look like a romanticized ancient god, but instead is a vulgar, effeminate youth who offers the viewer wine from a shallow goblet. This portrayal of Bacchus as a young man dressed as the god is consistent with the theatricality and staging of all of Caravaggio’s paintings. In my analysis, I identified this unusual depiction of Bacchus as a young man, but I did not initially notice the prominent sensuality of the Bacchus figure. Perhaps this is because I assumed that the model’s body language and flushed face were painted to show his drunkenness, as Bacchus is the god of wine. I am pleased with my analysis, especially because I know that I could not possibly observe everything in the painting because of the limited time I had to study the painting.

I have seen many Caravaggio paintings, usually during art history classes in museums around Rome and Florence, and I have always been interested in learning about the subjects of the paintings and how the artist pioneered a new style in art. However, it is a completely different experience to stand in front of a painting by myself and write down everything that I observe. On my own, I can decide which parts of the painting I am drawn to instead of learning what scholars believe or even what the artist intended to paint. When I am forced to look at a painting by myself, I am free to interpret the art in a way that makes it personal and more intimate. This is how Bacchus introduced me to my Caravaggio.

I have stumbled upon a Caravaggio! Bacchus, with his glass of wine and headdress of leaves, looks up at me from the tiny canvas. I was drawn to this small painting on a small table because of the dark background that contrasts with all of the bright paintings around it. The main figure, a young man dressed in a white toga, is posing for a portrait. He is fair-skinned, but his cheeks and face are flushed, probably the result of his indulgence in the wine that he is holding. A bounty of fruits is placed on the table in front of him and he wears a headdress of leaves. His left hand lightly grips a large glass of red wine as he reclines slightly to his right. His youthful face shows no sign of distress or unhappiness. I look around the room and I am surprised to see another Caravaggio painting, this time with Medusa as his subject, on display behind me. I quickly scan this image, trying to record it in my memory, before turning back to Bacchus. I am most interested in how much he resembles a real human boy. He is a beautiful boy, but he does not have the idealized, mature face that I expect from an artist portraying a god. After my limited viewing of the painting, I conclude that the painting is a portrait of the god Bacchus who is enjoying himself, as usual, by partaking of wine and a bountiful selection of fruits.

My surprise at finding a Caravaggio has inspired me to learn more about this particular painting. Scholars have hailed this piece as a prime example of Caravaggio’s developing talent with realism. His Bacchus does not look like a romanticized ancient god, but instead is a vulgar, effeminate youth who offers the viewer wine from a shallow goblet. This portrayal of Bacchus as a young man dressed as the god is consistent with the theatricality and staging of all of Caravaggio’s paintings. In my analysis, I identified this unusual depiction of Bacchus as a young man, but I did not initially notice the prominent sensuality of the Bacchus figure. Perhaps this is because I assumed that the model’s body language and flushed face were painted to show his drunkenness, as Bacchus is the god of wine. I am pleased with my analysis, especially because I know that I could not possibly observe everything in the painting because of the limited time I had to study the painting.

I have seen many Caravaggio paintings, usually during art history classes in museums around Rome and Florence, and I have always been interested in learning about the subjects of the paintings and how the artist pioneered a new style in art. However, it is a completely different experience to stand in front of a painting by myself and write down everything that I observe. On my own, I can decide which parts of the painting I am drawn to instead of learning what scholars believe or even what the artist intended to paint. When I am forced to look at a painting by myself, I am free to interpret the art in a way that makes it personal and more intimate. This is how Bacchus introduced me to my Caravaggio.

Creative Writing #11

The mass surged forward, taking me along for the ride, through the security checkpoint, past the souvenir shop, past the ornate doors, into the grand church. The crowd dispersed, people walking in every direction, cameras at the ready, taking pictures of everything they saw so they could record now, observe later. I heard tour guides reciting a two minute summary of the history and architecture of the church as their group trailed behind them, barely pausing to look around at the sculptures and paintings that surrounded them. I wandered to the high altar at the far end of the church and stopped. Directly in front of me was a colossal, bronze canopy with twisted columns supporting sculpted angels on the top. It was the baldacchino of St. Peter’s, the main showpiece of the basilica.

I walked around the baldacchino, stooping to look at the Barberini family crests that decorated the base and craning my neck to see the bronze tassels that hung from the canopy. After I studied the structure close-up, I stepped back to appreciate the scale and design of the baldacchino, but I constantly moved to avoid blocking the other visitors who pushed past me to get a closer look at the baldacchino. Almost all of the tourists, presumably some Catholics and some art lovers of various faiths, looked up at the baldacchino and the dome of St. Peter’s in awe. They pointed up at paintings and looked down at the marble floors with expressions of amazement on their faces. A young man with a guidebook in his hands spun around trying to figure out what he should see first. Everywhere I turned, I could see people taking pictures and admiring the expensive and exquisite art on the walls. Nevertheless, there was something missing from this church. There were hundreds of people, but none of them were praying in this church. The basilica clearly conveyed a message to visitors, but it was not a message of piety or reverence for the holiest saints and God. Instead, modern pilgrims came to see the material representations of these figures. These visitors did not come to worship God, but instead were worshipping the art that was created in his name. They were not in awe of God’s miracles and creations in this elaborate church; they were in awe of the Catholic Church’s power and wealth. I left the basilica wondering if anyone felt comfortable enough in the lavishly decorated church to close their eyes for a moment to pray there.

My experience in the largest church in the world made me think about the smallest church that I have ever visited. On a recent trip to Venice, I went on a tour of the islands near the city. Our tour boat took us to Murano and Burano to see the famed glass blowers and then we were taken to a minuscule island that I had never heard of before our visit. We were given one hour to explore Torcello, an island that features one of the oldest churches in the Venice area. Our tour guide explained that the cathedral is the only interesting sight on the island and we could not get lost on our way there because there is only one road in Torcello. I meandered through the town, following the only road that was paved alongside a small canal that ran the length of the island. I reached the other end of the island and I saw a modest church nestled on the shore, overlooking the water. It was built with large stones and had a simple colonnade that decorated the façade of the small building. Before entering the church, I walked along the shore of Torcello, watching the light sparkle on the deep blue surface of the water and listening to the gentle lapping of the waves in the lagoon. Twenty minutes later, I entered the small church to look around. There was only one small painting in the church with small lanterns emitting a dim light that hardly illuminated the stone walls and the wooden pews. The single room was completely silent. There were no clicks or quick flashes of lights from cameras. There was no marble floor that loudly echoed the footsteps of visitors. I sat in the front of the church by myself, feeling calm and relaxed in this haven by the water. I did not recite any of the Catholic prayers that I know so well, nor did I kneel in front of the crucifix on the altar. I silently meditated on my travels thus far and I thought about all of the objects I had seen in countless museums and churches. I wondered if I would remember any of those priceless works of art or if I would only remember how I felt about them. I finally left the church and started walking back to the dock on the other side of the island. As I wandered down the single road, I realized that this tiny church on this remote island was one of my favorite churches I had seen during the entire trip. It was not gilded or decorated with the works of famous artists, but it invited me in with its humble interior of rock and wood. There was no gift shop or large piazza surrounding the building, but I could contemplate issues of spirituality and faith next to the bluest waters in the serene lagoon beside the church. This cathedral did not have a message of power or authority, but instead was a personal place of worship for all visitors.

On my visits to both St. Peter’s basilica and the Church of Santa Fosca in Torcello, I was a pilgrim searching for a place in which I would be inspired and could strengthen my faith. Both churches were built in order to fulfill specific purposes. They were both monuments built to honor the good works of two saints with unwavering faith. St. Peter’s basilica, the largest church in the world, has become a symbol of the influence and strength of the Catholic Church while the Church of Santa Fosca is preserved as an inviting, modest house of worship. As a pilgrim, I experienced a more profound religious awakening in the little church on the shore of Torcello.

I walked around the baldacchino, stooping to look at the Barberini family crests that decorated the base and craning my neck to see the bronze tassels that hung from the canopy. After I studied the structure close-up, I stepped back to appreciate the scale and design of the baldacchino, but I constantly moved to avoid blocking the other visitors who pushed past me to get a closer look at the baldacchino. Almost all of the tourists, presumably some Catholics and some art lovers of various faiths, looked up at the baldacchino and the dome of St. Peter’s in awe. They pointed up at paintings and looked down at the marble floors with expressions of amazement on their faces. A young man with a guidebook in his hands spun around trying to figure out what he should see first. Everywhere I turned, I could see people taking pictures and admiring the expensive and exquisite art on the walls. Nevertheless, there was something missing from this church. There were hundreds of people, but none of them were praying in this church. The basilica clearly conveyed a message to visitors, but it was not a message of piety or reverence for the holiest saints and God. Instead, modern pilgrims came to see the material representations of these figures. These visitors did not come to worship God, but instead were worshipping the art that was created in his name. They were not in awe of God’s miracles and creations in this elaborate church; they were in awe of the Catholic Church’s power and wealth. I left the basilica wondering if anyone felt comfortable enough in the lavishly decorated church to close their eyes for a moment to pray there.

My experience in the largest church in the world made me think about the smallest church that I have ever visited. On a recent trip to Venice, I went on a tour of the islands near the city. Our tour boat took us to Murano and Burano to see the famed glass blowers and then we were taken to a minuscule island that I had never heard of before our visit. We were given one hour to explore Torcello, an island that features one of the oldest churches in the Venice area. Our tour guide explained that the cathedral is the only interesting sight on the island and we could not get lost on our way there because there is only one road in Torcello. I meandered through the town, following the only road that was paved alongside a small canal that ran the length of the island. I reached the other end of the island and I saw a modest church nestled on the shore, overlooking the water. It was built with large stones and had a simple colonnade that decorated the façade of the small building. Before entering the church, I walked along the shore of Torcello, watching the light sparkle on the deep blue surface of the water and listening to the gentle lapping of the waves in the lagoon. Twenty minutes later, I entered the small church to look around. There was only one small painting in the church with small lanterns emitting a dim light that hardly illuminated the stone walls and the wooden pews. The single room was completely silent. There were no clicks or quick flashes of lights from cameras. There was no marble floor that loudly echoed the footsteps of visitors. I sat in the front of the church by myself, feeling calm and relaxed in this haven by the water. I did not recite any of the Catholic prayers that I know so well, nor did I kneel in front of the crucifix on the altar. I silently meditated on my travels thus far and I thought about all of the objects I had seen in countless museums and churches. I wondered if I would remember any of those priceless works of art or if I would only remember how I felt about them. I finally left the church and started walking back to the dock on the other side of the island. As I wandered down the single road, I realized that this tiny church on this remote island was one of my favorite churches I had seen during the entire trip. It was not gilded or decorated with the works of famous artists, but it invited me in with its humble interior of rock and wood. There was no gift shop or large piazza surrounding the building, but I could contemplate issues of spirituality and faith next to the bluest waters in the serene lagoon beside the church. This cathedral did not have a message of power or authority, but instead was a personal place of worship for all visitors.

On my visits to both St. Peter’s basilica and the Church of Santa Fosca in Torcello, I was a pilgrim searching for a place in which I would be inspired and could strengthen my faith. Both churches were built in order to fulfill specific purposes. They were both monuments built to honor the good works of two saints with unwavering faith. St. Peter’s basilica, the largest church in the world, has become a symbol of the influence and strength of the Catholic Church while the Church of Santa Fosca is preserved as an inviting, modest house of worship. As a pilgrim, I experienced a more profound religious awakening in the little church on the shore of Torcello.

Monday, October 15, 2007

Creative Writing #15

After I discovered many of his works in churches, museums, and piazzas across Rome, I became a devoted admirer of Gian Lorenzo Bernini. While many of his sculptures are recognizable because of their distinctly Bernini-esque qualities, they each involve the viewer in a unique way. The Ecstasy of Beata Ludovica Albertoni, located in San Francesco a Ripa, and the Ecstasy of Saint Theresa, in Santa Maria della Vittoria, are two prominent examples of how Bernini portrayed two similar stories that affect the viewer in completely different ways.

The modest church San Francesco a Ripa is an unlikely setting for one of Bernini’s famed sculptures. It is an intensely quiet church, one of the few churches in Rome that is not constantly invaded by an endless parade of tourists. As my eyes adjusted to the dimly lit interior, I saw only a few paintings in the small side chapels. I wandered through the church into a dark chapel that contained the Ecstasy of Beata Ludovica Albertoni. I was surprised to see that this sculpture by the beloved artist was not prominently displayed, but instead was placed in an unmarked chapel.

When I looked up at the sculpture, my eyes were immediately drawn to the subject’s face, which was illuminated by a gentle yellow light coming from above. Her head was rolled back and her mouth partly open. Her whole face was contorted in an expression that I interpreted to be intense pain, but I was confused when I remembered the name of the sculpture. Her passionate expression was not supposed to convey her pain, but instead Bernini was portraying Ludovica Albertoni’s overwhelming spiritual ecstasy. I studied her face again and I decided that this was unlike any holy scene I had seen in religious paintings and sculptures. I felt slightly uncomfortable looking directly at her face, like I was intruding on an intensely private moment of overwhelming pleasure, spiritual or otherwise. Even the seraphim in the corner of the chapel, that I learned were not part of Bernini’s original design, did not participate in this private scene. In the dark chapel, the yellow light that shined on the sculpture seemed to be part of the art as well. At first glance, I assumed that there was a light that was placed behind the sculpture so that it would appear that rays of sunlight were coming from the heavens above to represent the subject’s overpowering moment of reverence and spiritual ecstasy. A lamp would also serve a more practical purpose in providing a source of light so that viewers could see the sculpture clearly in the dimly lit church. I was told that Bernini deliberately placed a hidden window behind the sculpture so that viewers would see the light shine on the subject’s face. After I left San Francesco a Ripa, I thought about this sculpture in comparison to the other Bernini works I had seen. I preferred this simple and subdued portrayal of a young woman, but it lacked the vivacity and theatricality of many of Bernini’s other masterpieces.

In contrast, the Ecstasy of Saint Theresa, in Santa Maria della Vittoria, was an ostentatious and dramatic portrayal of a similar scene, a woman in spiritual ecstasy. The Ecstasy of Saint Theresa was displayed in a bright, stage-like chapel bordered by colored marble. In this church, viewers were invited to admire the sculpture and the architecture that surrounded it. For this sculpture, the light was also a significant part of the viewing experience. However, the light distracted me from the sculpted figures because the light was the most striking part of the sculpture. The gilded rays of sunshine behind the sculpture brightened the natural light from windows in the ceiling into a more brilliant gold color. Nevertheless, when I looked at Saint Theresa’s face, I was reminded of the Ecstasy of Beata Ludovica Albertoni as I saw the unmistakable expression of pain etched on her face. Once again, I realized that I was mistaken because the sculpture was meant to show her spiritual ecstasy. I was distracted again from the two sculpted figures, Saint Theresa and an angel, by the placement of Saint Theresa in the chapel. She was resting on clouds that floated above the bottom of the chapel, which added to the theatricality of the sculpture. As I left the church, I saw a group of tourists make their way towards the sculpture.

After viewing both the Ecstasy of Beata Ludovica Albertoni and the Ecstasy of Saint Theresa, I realized that a sculpture’s surroundings often influence the art viewing experience. If the two sculptures were switched, the viewer’s experience would have been completely changed. The Ecstasy of Saint Theresa was an elaborate display of Bernini’s artistic skill and his ability to entertain viewers. The colorful marble and gilding around the sculpture enhance its grandiosity. Bernini’s Ecstasy of Beata Ludovica Albertoni is a more mature and humble portrayal of a private moment of spiritual ecstasy that does not attract much attention in the dimly lit San Francesco a Ripa. Both sculptures are valuable works of art that display Bernini’s unique talent of visually presenting a story in motion to admiring viewers.

The modest church San Francesco a Ripa is an unlikely setting for one of Bernini’s famed sculptures. It is an intensely quiet church, one of the few churches in Rome that is not constantly invaded by an endless parade of tourists. As my eyes adjusted to the dimly lit interior, I saw only a few paintings in the small side chapels. I wandered through the church into a dark chapel that contained the Ecstasy of Beata Ludovica Albertoni. I was surprised to see that this sculpture by the beloved artist was not prominently displayed, but instead was placed in an unmarked chapel.

When I looked up at the sculpture, my eyes were immediately drawn to the subject’s face, which was illuminated by a gentle yellow light coming from above. Her head was rolled back and her mouth partly open. Her whole face was contorted in an expression that I interpreted to be intense pain, but I was confused when I remembered the name of the sculpture. Her passionate expression was not supposed to convey her pain, but instead Bernini was portraying Ludovica Albertoni’s overwhelming spiritual ecstasy. I studied her face again and I decided that this was unlike any holy scene I had seen in religious paintings and sculptures. I felt slightly uncomfortable looking directly at her face, like I was intruding on an intensely private moment of overwhelming pleasure, spiritual or otherwise. Even the seraphim in the corner of the chapel, that I learned were not part of Bernini’s original design, did not participate in this private scene. In the dark chapel, the yellow light that shined on the sculpture seemed to be part of the art as well. At first glance, I assumed that there was a light that was placed behind the sculpture so that it would appear that rays of sunlight were coming from the heavens above to represent the subject’s overpowering moment of reverence and spiritual ecstasy. A lamp would also serve a more practical purpose in providing a source of light so that viewers could see the sculpture clearly in the dimly lit church. I was told that Bernini deliberately placed a hidden window behind the sculpture so that viewers would see the light shine on the subject’s face. After I left San Francesco a Ripa, I thought about this sculpture in comparison to the other Bernini works I had seen. I preferred this simple and subdued portrayal of a young woman, but it lacked the vivacity and theatricality of many of Bernini’s other masterpieces.

In contrast, the Ecstasy of Saint Theresa, in Santa Maria della Vittoria, was an ostentatious and dramatic portrayal of a similar scene, a woman in spiritual ecstasy. The Ecstasy of Saint Theresa was displayed in a bright, stage-like chapel bordered by colored marble. In this church, viewers were invited to admire the sculpture and the architecture that surrounded it. For this sculpture, the light was also a significant part of the viewing experience. However, the light distracted me from the sculpted figures because the light was the most striking part of the sculpture. The gilded rays of sunshine behind the sculpture brightened the natural light from windows in the ceiling into a more brilliant gold color. Nevertheless, when I looked at Saint Theresa’s face, I was reminded of the Ecstasy of Beata Ludovica Albertoni as I saw the unmistakable expression of pain etched on her face. Once again, I realized that I was mistaken because the sculpture was meant to show her spiritual ecstasy. I was distracted again from the two sculpted figures, Saint Theresa and an angel, by the placement of Saint Theresa in the chapel. She was resting on clouds that floated above the bottom of the chapel, which added to the theatricality of the sculpture. As I left the church, I saw a group of tourists make their way towards the sculpture.

After viewing both the Ecstasy of Beata Ludovica Albertoni and the Ecstasy of Saint Theresa, I realized that a sculpture’s surroundings often influence the art viewing experience. If the two sculptures were switched, the viewer’s experience would have been completely changed. The Ecstasy of Saint Theresa was an elaborate display of Bernini’s artistic skill and his ability to entertain viewers. The colorful marble and gilding around the sculpture enhance its grandiosity. Bernini’s Ecstasy of Beata Ludovica Albertoni is a more mature and humble portrayal of a private moment of spiritual ecstasy that does not attract much attention in the dimly lit San Francesco a Ripa. Both sculptures are valuable works of art that display Bernini’s unique talent of visually presenting a story in motion to admiring viewers.

Monday, October 8, 2007

Creative Writing #1

On my first visit to the Pantheon, I decided to also explore the world-famous Piazza della Rotonda. The square was bustling with tourists coming to visit the awe-inspiring temple, locals leaving gelaterias with their large cones full of brightly colored gelato and couples who walked purposefully through the piazza without even looking at the sights surrounding them. After wandering through the square, trying to avoid the bright glare of the sign directing tourists to the nearby McDonald’s, I found a small, darkened cartoleria that had a modest display of paper and journals that I could see through the closed window. I decided that I would return to this place soon just to browse their selection of journals so that I could possibly find one for class.

The next time I saw the cartoleria was at night, after a walk through Rome with twenty other students in my class. After our teacher recommended that we visit the small store, our class rushed the store and I was left outside wondering if I wanted to join in the chaotic search for a journal in the cartoleria. I ultimately decided to come back later when I could spend time in the cartoleria by myself, trying to choose which journal was the perfect one to hold all of my thoughts and observations about Rome. I returned the next evening, before dark.

When I stepped into the store, I first noticed that it was not a brightly lit area with different types of journals prominently on display, as I had anticipated. Instead, I found a dim, small space with one young woman working at the counter. I looked in the door to the tiny store and was surprised by the total lack of noise inside. Outside, in the piazza, restaurant patrons were conversing loudly and tourists were commenting excitedly on the Pantheon, but the inside of the store was completely silent. I could almost hear the faint swish of the cashier turning the pages of the book she was reading. I cautiously walked into the store, not wanting to disturb the rare tranquil silence I found in this haven near the crowded piazza. What I found inside was a book lover’s dream. The entire cartoleria was lined with antique-looking, dark wooden shelves that each held a stock of leather-covered journals. The journals were arranged by type and size. Lined, unlined, large, small, dark leather, lighter colored. I was overwhelmed by the smell of leather that seemed to envelop me as I stepped towards the shelves to have a closer look. I spent at least an hour in the store, just looking at all of the different types of journals and thinking about what I should write in them. I do not usually write in a journal, but I imagined myself sitting along the Tiber writing about the people and events that I would see. I would open my leather journal and be inspired to fill the blank, ivory pages with observations and my thoughts. However, I was quickly jerked back to reality when I saw that this dream that was centered around this leather journal would cost me at least 60 euro. I decided that the fantasy was not worth that much, especially when I considered that this one journal was equivalent to giving up 30 cones of gelato.

I decided that I needed to leave the cartoleria before I made a purchase that I would regret later, so I put down the beautifully crafted, dark brown journal and turned to leave. Just as I was about to walk out the door, a brightly colored pattern caught my eye. On a table in the front of the store, there was a small stack of paper-covered journals in various colors and patterns. They did not incite the same longing to write in them as the leather-bound journals, but they were elegant and lovely in their own way. I browsed through this stack of less expensive journals and finally found a journal that was decorated with multi-colored flowers with gold accents that made the flowers shine. The gold work reminded me of the gilded artwork that we saw so many times in churches that I reminded. I took the journal to the cashier and finally broke the silence with my embarrassingly bad Italian to ask her how much the small book cost. After paying more than I ever had before for a blank journal, I walked out of the store into the dark, chaotic piazza clutching my journal and thinking about what I should write for my inaugural journal entry.

The next time I saw the cartoleria was at night, after a walk through Rome with twenty other students in my class. After our teacher recommended that we visit the small store, our class rushed the store and I was left outside wondering if I wanted to join in the chaotic search for a journal in the cartoleria. I ultimately decided to come back later when I could spend time in the cartoleria by myself, trying to choose which journal was the perfect one to hold all of my thoughts and observations about Rome. I returned the next evening, before dark.

When I stepped into the store, I first noticed that it was not a brightly lit area with different types of journals prominently on display, as I had anticipated. Instead, I found a dim, small space with one young woman working at the counter. I looked in the door to the tiny store and was surprised by the total lack of noise inside. Outside, in the piazza, restaurant patrons were conversing loudly and tourists were commenting excitedly on the Pantheon, but the inside of the store was completely silent. I could almost hear the faint swish of the cashier turning the pages of the book she was reading. I cautiously walked into the store, not wanting to disturb the rare tranquil silence I found in this haven near the crowded piazza. What I found inside was a book lover’s dream. The entire cartoleria was lined with antique-looking, dark wooden shelves that each held a stock of leather-covered journals. The journals were arranged by type and size. Lined, unlined, large, small, dark leather, lighter colored. I was overwhelmed by the smell of leather that seemed to envelop me as I stepped towards the shelves to have a closer look. I spent at least an hour in the store, just looking at all of the different types of journals and thinking about what I should write in them. I do not usually write in a journal, but I imagined myself sitting along the Tiber writing about the people and events that I would see. I would open my leather journal and be inspired to fill the blank, ivory pages with observations and my thoughts. However, I was quickly jerked back to reality when I saw that this dream that was centered around this leather journal would cost me at least 60 euro. I decided that the fantasy was not worth that much, especially when I considered that this one journal was equivalent to giving up 30 cones of gelato.

I decided that I needed to leave the cartoleria before I made a purchase that I would regret later, so I put down the beautifully crafted, dark brown journal and turned to leave. Just as I was about to walk out the door, a brightly colored pattern caught my eye. On a table in the front of the store, there was a small stack of paper-covered journals in various colors and patterns. They did not incite the same longing to write in them as the leather-bound journals, but they were elegant and lovely in their own way. I browsed through this stack of less expensive journals and finally found a journal that was decorated with multi-colored flowers with gold accents that made the flowers shine. The gold work reminded me of the gilded artwork that we saw so many times in churches that I reminded. I took the journal to the cashier and finally broke the silence with my embarrassingly bad Italian to ask her how much the small book cost. After paying more than I ever had before for a blank journal, I walked out of the store into the dark, chaotic piazza clutching my journal and thinking about what I should write for my inaugural journal entry.

Thursday, September 20, 2007

"Must Be Americans..."

Almost every day for at least three weeks, we talked about ordering a grande gelato from our favorite gelateria, San Crispino, on our last night in Rome. It's not that we have been depriving ourselves of gelato. In fact, I can't think of a day when I didn't have one cone of gelato (or two or three cones). But those were always piccolos and tonight is definitely a grande night. After tossing our three coins in the Trevi Fountain to ensure our return to Rome, Erina, Gabrielle, Megan and I went to San Crispino's and ordered the largest size of gelato they had. At first, Megan started to back out. She claimed that she could not eat that much gelato, no matter what she promised before. She said that we would all feel sick, which isn't the best feeling when you are going to board a plane in a few hours. A promise is a promise, we reminded her and she eventually caved in. We each sheepishly asked for the biggest size they had and filled it with our favorite flavors. We walked home slowly, talking about our favorite moments in Rome.

It wasn't until we were halfway home that we noticed how people around us were staring. Families seated at outdoor tables in restaurants stared and pointed at our massive bowls of gelato. Two men walking past us did a double-take and one of them said, quite loudly, "Must be Americans." We all laughed and looked down at our 7 euro bowls of gelato that we couldn't finish. We really did look ridiculous, but a promise is a promise.

It wasn't until we were halfway home that we noticed how people around us were staring. Families seated at outdoor tables in restaurants stared and pointed at our massive bowls of gelato. Two men walking past us did a double-take and one of them said, quite loudly, "Must be Americans." We all laughed and looked down at our 7 euro bowls of gelato that we couldn't finish. We really did look ridiculous, but a promise is a promise.

No foto? No problem. (Travel Writing #23)

The Dance

A flash of light catches my eye. I move onto the balcony for a closer look. Down below, in the Campo de Fiori, a crowd is building. Six figures are in the center, dancing with sticks on fire. The idea of making art from something dangerous is both frightening and mesmerizing. The flames blur together, a circle of bright orange in the dark. Someone is playing loud music nearby. The thumping beat intensifies the performance as the dancers begin to twirl. They weave between each other, always waving their sticks high above their heads so that everyone can see. One man steps away from the other dancers and breathes fire as the onlookers applaud. I watch from high above, captivated by the light.

Wrong Turn

I laugh and talk loudly with friends as we try to find our way home in the dark. Left here, no, straight ahead. We take a wrong turn and wander into an enormous piazza. Here it is on the map. I am at St. Peter’s, the largest church in the world. Quiet! This is a place of worship. The piazza welcomes pilgrims who travel for days, months, years. I see the outline of the glowing basilica, illuminated by lanterns from within. Rows of white columns encircle the piazza, isolating this space from the world outside. Voices drift farther away from where I am standing still. The church is closed, but I can pray here. I close my eyes and hear the rush of water from the fountain to my right. This is my holy place.

I have found my home

In an unfamiliar place.

Alone in the dark.

In the Sky

We walk in groups of twos and threes playing follow the leader. He walks quickly and confidently through busy streets. I walk, stop, inch forward, stop, no cars, run. It feels like we have been walking for hours. We stop in front of a stone path that leads up a hill. There is a wrought iron gate at the end, but it is locked. Locks were made to guard precious things. What is this gate hiding? Keep moving forward, always forward. I am breathing heavily now. Just a little bit farther, I think. I hope. We finally reach the top and turn left, past the gate. Try to find another way in. There is another path, now stairs. We are quiet, no breath left for idle chatter. We trudge up flights of stairs, and finally we are here. This cannot be a part of Rome. There are no buildings, no crowds of tourists, no Vespas zooming past us. This is the most green I have seen in Rome. A grove of orange trees offers us shade from the merciless sun, but still we are moving. He leads us through the park, to a stone ledge on the other side. We peer over the edge. We can see all of Rome from this vantage point. We can see every monument, even people walking through the city. I have reached the highest point.

A flash of light catches my eye. I move onto the balcony for a closer look. Down below, in the Campo de Fiori, a crowd is building. Six figures are in the center, dancing with sticks on fire. The idea of making art from something dangerous is both frightening and mesmerizing. The flames blur together, a circle of bright orange in the dark. Someone is playing loud music nearby. The thumping beat intensifies the performance as the dancers begin to twirl. They weave between each other, always waving their sticks high above their heads so that everyone can see. One man steps away from the other dancers and breathes fire as the onlookers applaud. I watch from high above, captivated by the light.

Wrong Turn

I laugh and talk loudly with friends as we try to find our way home in the dark. Left here, no, straight ahead. We take a wrong turn and wander into an enormous piazza. Here it is on the map. I am at St. Peter’s, the largest church in the world. Quiet! This is a place of worship. The piazza welcomes pilgrims who travel for days, months, years. I see the outline of the glowing basilica, illuminated by lanterns from within. Rows of white columns encircle the piazza, isolating this space from the world outside. Voices drift farther away from where I am standing still. The church is closed, but I can pray here. I close my eyes and hear the rush of water from the fountain to my right. This is my holy place.

I have found my home

In an unfamiliar place.

Alone in the dark.

In the Sky

We walk in groups of twos and threes playing follow the leader. He walks quickly and confidently through busy streets. I walk, stop, inch forward, stop, no cars, run. It feels like we have been walking for hours. We stop in front of a stone path that leads up a hill. There is a wrought iron gate at the end, but it is locked. Locks were made to guard precious things. What is this gate hiding? Keep moving forward, always forward. I am breathing heavily now. Just a little bit farther, I think. I hope. We finally reach the top and turn left, past the gate. Try to find another way in. There is another path, now stairs. We are quiet, no breath left for idle chatter. We trudge up flights of stairs, and finally we are here. This cannot be a part of Rome. There are no buildings, no crowds of tourists, no Vespas zooming past us. This is the most green I have seen in Rome. A grove of orange trees offers us shade from the merciless sun, but still we are moving. He leads us through the park, to a stone ledge on the other side. We peer over the edge. We can see all of Rome from this vantage point. We can see every monument, even people walking through the city. I have reached the highest point.

Wednesday, September 12, 2007

The Lucky Spot

I am sitting in the luckiest spot in the Sistine Chapel. Can I have a moment more perfect than this one? According to Gabrielle, this seat on the bench underneath Perugino's Giving of the Keys to St. Peter is the luckiest place for papal hopefuls to sit during conclaves. Pope Julius II was sitting here during the conclave when he was elected and ever since then, it is known as the "lucky spot." I don't have a desire to be the Pope one day (for obvious reasons), but it feels special and meaningful to be looking up at the Sistine chapel ceiling from this historically significant spot.

After looking at the incomparable paintings on the walls and the ceiling, of course, I'm thinking about what else I need to do here before my time is up. This may be the only time that I am ever in the Sistine chapel for more than a few minutes. I am certain that if I do come again, I will be pushed through the room quickly by a crowd of tourists, with barely a few minutes to glance at all the art. What can I do in this overwhelmingly beautiful room that was created for the Church? I take a few more minutes to look around and then I pray.

After looking at the incomparable paintings on the walls and the ceiling, of course, I'm thinking about what else I need to do here before my time is up. This may be the only time that I am ever in the Sistine chapel for more than a few minutes. I am certain that if I do come again, I will be pushed through the room quickly by a crowd of tourists, with barely a few minutes to glance at all the art. What can I do in this overwhelmingly beautiful room that was created for the Church? I take a few more minutes to look around and then I pray.

Creative Writing #4

I was chatting with a friend as we walked hurriedly through the brightly lit staircase. We did not see the signs that the group was following. Instead, we talked about our schedule for the next day and the church that we visited early that morning. We walked quickly through the small door that the rest of the group quickly passed through. I walked through this portal into a room and I was slightly surprised at the abrupt drop in temperature. Suddenly, I was overwhelmed by a wave of color that surrounded me. Royal blues, deep crimson and sparkling gold shone from the hundreds of paintings on the walls and the ceiling, surrounding me in a treasure chest of color. I instinctively looked up and saw images that I have seen a thousand times crowded together with thousands of figures across the length of the small chapel. I was standing alone under one of the most celebrated artistic masterpieces in the world: Michelangelo’s ceiling of the Sistine chapel.

I walked into the chapel, still straining my neck to see some of the panels above me: the Creation of Adam, the Creation of Eve, and the Flood. These scenes were smaller and closer together than I expected, which made the entire chapel look smaller than I imagined it would be. I heard the burly guard who accompanied us growling “no photo” but I was not bothered. How could I capture all of this art, color and light in a series of photos that could only record a small, flat image? I could not waste precious time in this room looking at all of the art through the small screen on my camera. I walked around the perimeter of the chapel, trying to comprehend the idea that I was seeing all of the paintings in the Sistine chapel without the interference of thousands of other people. I could stand in the center of the chapel and look up The Final Judgment without being jostled and pushed through to the exit by the constantly moving, noisy mass of visitors. In fact, the quiet murmur of a few students sharing their knowledge of the paintings was the only sound in the room. Some students stood together in small groups while others wandered around by themselves, all stopping every few minutes to study a painting on the wall or craning their necks to see all of the frescoes on the high ceiling. Walking backwards towards the benches that lined the walls, I stared up at the images on the ceiling, trying to identify the figures and subjects that I saw in different scenes. I sat on the plexiglass-covered stone bench and I decided to write about this experience in my journal while I was in the moment.

I pulled my journal out of my bag, which took a few minutes since I did not want to stop looking around while I attempted to open my purse, and I started to write. I wrote about the bright colors and the surreal feeling of being in the Sistine chapel, but I was not satisfied with this latest entry. As I looked down at the handwritten words on the white page, they seemed inadequate; too small and simple to convey my excitement and wonder. I could not describe the exact shade of the brightest blue or how the light brightened some paintings while others were left in darker shadow. I could not explain the feeling of looking up at the Creation of Adam and wondering if Michelangelo would ever know how iconic this work would become for generations centuries in the future.

Surprisingly, I was also overcome with a desire to pray in this beautiful chapel. I am not very religious, but as I looked up at all of the art commissioned by popes and completed by a pious artist who created the stunning art as an offering to God, I was motivated by the beauty around me to give thanks to God or at least the belief in Him that has inspired so many artists to decorate the many churches around Rome. At this moment, I knew that I could never describe the emotion that overwhelmed me when I looked up at the paintings around me because it was deeply personal and private. Although I do not have a detailed record of all that I saw in the Sistine chapel, I am satisfied with my own memories of the night that I finally understood how much beauty can inspire people to believe that there must be a power greater than man.

I walked into the chapel, still straining my neck to see some of the panels above me: the Creation of Adam, the Creation of Eve, and the Flood. These scenes were smaller and closer together than I expected, which made the entire chapel look smaller than I imagined it would be. I heard the burly guard who accompanied us growling “no photo” but I was not bothered. How could I capture all of this art, color and light in a series of photos that could only record a small, flat image? I could not waste precious time in this room looking at all of the art through the small screen on my camera. I walked around the perimeter of the chapel, trying to comprehend the idea that I was seeing all of the paintings in the Sistine chapel without the interference of thousands of other people. I could stand in the center of the chapel and look up The Final Judgment without being jostled and pushed through to the exit by the constantly moving, noisy mass of visitors. In fact, the quiet murmur of a few students sharing their knowledge of the paintings was the only sound in the room. Some students stood together in small groups while others wandered around by themselves, all stopping every few minutes to study a painting on the wall or craning their necks to see all of the frescoes on the high ceiling. Walking backwards towards the benches that lined the walls, I stared up at the images on the ceiling, trying to identify the figures and subjects that I saw in different scenes. I sat on the plexiglass-covered stone bench and I decided to write about this experience in my journal while I was in the moment.

I pulled my journal out of my bag, which took a few minutes since I did not want to stop looking around while I attempted to open my purse, and I started to write. I wrote about the bright colors and the surreal feeling of being in the Sistine chapel, but I was not satisfied with this latest entry. As I looked down at the handwritten words on the white page, they seemed inadequate; too small and simple to convey my excitement and wonder. I could not describe the exact shade of the brightest blue or how the light brightened some paintings while others were left in darker shadow. I could not explain the feeling of looking up at the Creation of Adam and wondering if Michelangelo would ever know how iconic this work would become for generations centuries in the future.

Surprisingly, I was also overcome with a desire to pray in this beautiful chapel. I am not very religious, but as I looked up at all of the art commissioned by popes and completed by a pious artist who created the stunning art as an offering to God, I was motivated by the beauty around me to give thanks to God or at least the belief in Him that has inspired so many artists to decorate the many churches around Rome. At this moment, I knew that I could never describe the emotion that overwhelmed me when I looked up at the paintings around me because it was deeply personal and private. Although I do not have a detailed record of all that I saw in the Sistine chapel, I am satisfied with my own memories of the night that I finally understood how much beauty can inspire people to believe that there must be a power greater than man.

Tuesday, September 11, 2007

Escaping My Former Self (Travel Writing #24)

As I sat in the airport waiting to board the plane to Amsterdam for the first leg of my trip to Italy, I fantasized about my imminent stay in Rome. I imagined myself strolling along the Tiber and then rushing past the Colisseum on my way to class. My limited Italian would not hold back my complete assimilation into Italian culture for five weeks as I lived in the heart of historic Rome. The ultimate test of my authenticity would be whether other tourists identified me as one of their own or as a local who had lived in Rome her entire life. My daydream was abruptly interrupted by the flight attendant’s announcement that the flight was boarding soon.

I quickly gathered my belongings and stood in line at the gate with the mass of people trying to board the plane. I looked around at my fellow travelers and I noticed that they were all Indian. Many of the women were dressed in traditional, brightly colored saris and were talking about what they would do first when they arrived in Mumbai, their final destination. As a second generation Sri Lankan-American, I had often made these trips back to my parents’ homeland where I stayed in the same place and did not explore the cities at all. I pitied these travelers because they were clearly not trying to have their own adventures in a new, exotic country. They would never venture out of their comfort zone to create a new cultural identity, like I would during my stay in Italy. I boarded the airplane and said goodbye to my old life.

After two weeks in Italy, I realized that assimilating into Italian culture would be much more difficult than I originally thought it would be. Everywhere I went, I was constantly reminded of how I was different from true Roman citizens. Indian men walked uncomfortably close behind me and whispered “hello, miss India” or “ciao, mama” as they passed by. A grocery store clerk handed me a bottle of curry powder while I stood in front of the selection of spices in the store, trying to find seasoning for my pasta. Even the server at San Crispino’s looked at me for a minute and asked, “where are you from?” as he handed me my cup of honey gelato that I had ordered completely in Italian just two minutes earlier. I was still desperately trying to be adventurous and truly belong in Rome, but I could not break through the cultural barrier that separated me from the authentic Romans who were never mistaken for tourists as they traversed the city.

Now I look back on my time in Rome and I know I was able to assimilate into Italian culture as fully as I ever could. I am still disappointed every time the baker at the forno asks for three euro in English after I order my tramezzino di prosciutto e fichi or when the purse vendors in the street try to attract my attention because they think that I am a wealthy tourist. Nevertheless, I have had more Roman adventures than I ever dreamed about and it is time for me to return home and embrace my Sri Lankan, American and now Italian sides.

I quickly gathered my belongings and stood in line at the gate with the mass of people trying to board the plane. I looked around at my fellow travelers and I noticed that they were all Indian. Many of the women were dressed in traditional, brightly colored saris and were talking about what they would do first when they arrived in Mumbai, their final destination. As a second generation Sri Lankan-American, I had often made these trips back to my parents’ homeland where I stayed in the same place and did not explore the cities at all. I pitied these travelers because they were clearly not trying to have their own adventures in a new, exotic country. They would never venture out of their comfort zone to create a new cultural identity, like I would during my stay in Italy. I boarded the airplane and said goodbye to my old life.

After two weeks in Italy, I realized that assimilating into Italian culture would be much more difficult than I originally thought it would be. Everywhere I went, I was constantly reminded of how I was different from true Roman citizens. Indian men walked uncomfortably close behind me and whispered “hello, miss India” or “ciao, mama” as they passed by. A grocery store clerk handed me a bottle of curry powder while I stood in front of the selection of spices in the store, trying to find seasoning for my pasta. Even the server at San Crispino’s looked at me for a minute and asked, “where are you from?” as he handed me my cup of honey gelato that I had ordered completely in Italian just two minutes earlier. I was still desperately trying to be adventurous and truly belong in Rome, but I could not break through the cultural barrier that separated me from the authentic Romans who were never mistaken for tourists as they traversed the city.

Now I look back on my time in Rome and I know I was able to assimilate into Italian culture as fully as I ever could. I am still disappointed every time the baker at the forno asks for three euro in English after I order my tramezzino di prosciutto e fichi or when the purse vendors in the street try to attract my attention because they think that I am a wealthy tourist. Nevertheless, I have had more Roman adventures than I ever dreamed about and it is time for me to return home and embrace my Sri Lankan, American and now Italian sides.

Monday, September 10, 2007

Thinking in Italian

In Italian class, we are taught how to say things like "I like" (Mi piace) or "I am" (Io sono), but we don't spend a lot of time learning the future or past tenses. Maybe this is because our time in Italy and Italian class is extremely limited, but I like to think it's because our teachers want us to learn how to be in the moment, no matter what we are doing. Instead of saying what we used to like or where we will be going, we have a chance to talk about what we are doing at that certain moment. Usually, I am frustrated when I don't know how to communicate exactly what I am thinking but I like this limitation.

Wednesday, September 5, 2007

A Moment of Tranquility

We are at the Basilica di Santo Quattro Coronati, in an ancient cloister in the middle of Rome. After walking through the busiest streets in Rome, I am shocked at how quiet and tranquil this cloister is. I am sitting on a dark stone bench listening to the only sound in the room (possibly the only sound in the building), the trickle of water from a twelfth century fountain in the center of the courtyard. I wonder if the quiet is due to the nuns' vow of silence or the seclusion of this small church high up above the bustling streets of Rome.

We were just told that this church dates back to 500 AD, which makes me wonder how much of this courtyard is really that old and how much has been recently added. I think it is safe to assume that the shrubs in tan plastic pots are recent additions. It is more difficult to guess when the painted patterns of red and green teardrops or the stained brown and yellow triangles were added to the underside of all the arches that frame the courtyard. There are also fragments of rocks on the wall, some with writing on it. These are probably from the excavations in the church that resulted in the discovery of all these ancient artifacts.

There is a sign that details the restoration efforts. It is fascinating to see the picture of an ancient column that was cleaned by laser. I usually think of restoration works as an expert using a delicate brush to carefully clear centuries of dirt from ruins, not the use of high-tech lasers to remove dirt quickly and efficiently.

There is one stone on the wall that is a mystery to me. In the center, there is the word(s?) LOCUSURICITFELICITATIS. It is strange because the words are carved almost haphazardly, like the carver was in a hurry to finish this particular inscription. The stone seems out of place next to smaller stones with lines of carefully carved inscriptions. Did the carver have a reason for rushing through this inscription? Was he less skilled than the carvers of the other stones I see?

I also find it strange that there is a small gift stand inside the cloister. After walking around the open courtyard, I see a table and a card stand with postcards and books on sale. Even though I know that we are still in Rome, it surprises me to see this particular part of the modern world in this quiet cloister. It seems intrusive, like it is disrupting the peace in this silent space.

We were just told that this church dates back to 500 AD, which makes me wonder how much of this courtyard is really that old and how much has been recently added. I think it is safe to assume that the shrubs in tan plastic pots are recent additions. It is more difficult to guess when the painted patterns of red and green teardrops or the stained brown and yellow triangles were added to the underside of all the arches that frame the courtyard. There are also fragments of rocks on the wall, some with writing on it. These are probably from the excavations in the church that resulted in the discovery of all these ancient artifacts.

There is a sign that details the restoration efforts. It is fascinating to see the picture of an ancient column that was cleaned by laser. I usually think of restoration works as an expert using a delicate brush to carefully clear centuries of dirt from ruins, not the use of high-tech lasers to remove dirt quickly and efficiently.

There is one stone on the wall that is a mystery to me. In the center, there is the word(s?) LOCUSURICITFELICITATIS. It is strange because the words are carved almost haphazardly, like the carver was in a hurry to finish this particular inscription. The stone seems out of place next to smaller stones with lines of carefully carved inscriptions. Did the carver have a reason for rushing through this inscription? Was he less skilled than the carvers of the other stones I see?

I also find it strange that there is a small gift stand inside the cloister. After walking around the open courtyard, I see a table and a card stand with postcards and books on sale. Even though I know that we are still in Rome, it surprises me to see this particular part of the modern world in this quiet cloister. It seems intrusive, like it is disrupting the peace in this silent space.

Monday, August 27, 2007

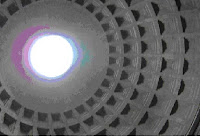

The Pantheon

After visiting the Pantheon and admiring its elegant design, the artist Michelangelo proclaimed “desegno angelico e non umano”, that it was the design of angels and not of man. Although it was built almost two thousand years ago with basic materials, the Pantheon is still revered as an architectural masterpiece. Despite numerous restorations and renovations over the past few centuries, the main building is largely intact and contains much of the ancient, original marble that was imported for the temple. The Pantheon as it is seen today is the result of the Roman emperor Hadrian’s substantial building program that included the construction of bridges, temples, monuments and even entire towns. In order to understand the history and significance of the Pantheon, it is important to first examine the man who is responsible for the building as it stands today.

Both Hadrian and his predecessor Trajan were from Italica, Hispania, in modern-day Spain. Hadrian’s provincial origins led to his reputation as a “man of the Empire, not the capital” which he proved with his extensive travels as emperor. The emperor who would be known simply as Hadrian was born Publius Aelius Hadrianus on January 24, 76 CE. Many of his ancestors served as magistrates and his most notable great-great-great-grandfather was a senator during the reign of Julius Caesar. When Hadrian’s father died in 85 CE, he became a ward of his second cousin, Marcus Ulpius Trajanus, known as Trajan. Trajan, a respected soldier, received orders to go to Rome and Hadrian was brought with him to the capital. Trajan eventually gained more power as a favorite of the Senate’s and eventually became the first non-Italian emperor of the Roman Empire. In order to strengthen his connection to Trajan, Hadrian eventually married Trajan’s great-niece, Sabina. By 101 CE, Hadrian had become a senator and started the break in tradition that resulted with more provincials gaining senate offices. Over the next several years, Hadrian built a successful career as an officer with victories that included the capture of Mesopotamia and the annexation of the Kingdom of Armenia. When Trajan died suddenly in 117, his wife Plotina declared that Trajan had formally adopted Hadrian on his death bed and named him as his successor. As a result, Hadrian was acclaimed emperor on August 11, 117 (Grabsky 135).

Both Hadrian and his predecessor Trajan were from Italica, Hispania, in modern-day Spain. Hadrian’s provincial origins led to his reputation as a “man of the Empire, not the capital” which he proved with his extensive travels as emperor. The emperor who would be known simply as Hadrian was born Publius Aelius Hadrianus on January 24, 76 CE. Many of his ancestors served as magistrates and his most notable great-great-great-grandfather was a senator during the reign of Julius Caesar. When Hadrian’s father died in 85 CE, he became a ward of his second cousin, Marcus Ulpius Trajanus, known as Trajan. Trajan, a respected soldier, received orders to go to Rome and Hadrian was brought with him to the capital. Trajan eventually gained more power as a favorite of the Senate’s and eventually became the first non-Italian emperor of the Roman Empire. In order to strengthen his connection to Trajan, Hadrian eventually married Trajan’s great-niece, Sabina. By 101 CE, Hadrian had become a senator and started the break in tradition that resulted with more provincials gaining senate offices. Over the next several years, Hadrian built a successful career as an officer with victories that included the capture of Mesopotamia and the annexation of the Kingdom of Armenia. When Trajan died suddenly in 117, his wife Plotina declared that Trajan had formally adopted Hadrian on his death bed and named him as his successor. As a result, Hadrian was acclaimed emperor on August 11, 117 (Grabsky 135).

Despite the centralization of power in Rome, Hadrian traveled extensively to tour the provinces and legions that safeguarded Rome. In fact, 13 of his 21 years in power were spent outside Italy in other provinces. He was distinctive as an emperor because he did not want to expand the Empire, as Trajan and many other emperors before him did, but instead he wanted to strengthen its boundaries (Grabsky 145). In 122, Hadrian initiated his building program with the construction of a wall to cover the 73 mile border between Britain and the Roman Empire. Hadrian’s Wall was a visible statement of Roman authority in that it served a barrier against small raids and isolated the Empire from other neighboring areas (Grabsky 150). During his travels, Hadrian made many improvements for various other provinces outside of Rome. He especially had a fondness for all things Greek. For instance, he wore a close-cropped beard usually associated with the ancient Greek philosophers, despite the tradition of clean-shaven emperors. He also declared himself a citizen of Athens and constructed several monuments while visiting the city. During his visit during the winter of 124 CE, Hadrian commissioned a new aqueduct, completed the temple of Zeus, ordered the construction of a new library and built a new quarter of town called Hadrianopolis. As a result of his extensive travels and his reputation as “the greekling,” some Italian subjects believed that Hadrian’s allegiance was to Athens, not Rome (Brown 57). In response, Hadrian launched a program of restoration and building projects within the capital. Within Rome, he built landmarks including the Temple of Venus and Rome, a temple to the deified Trajan, and the Castel Sant’ Angelo, which he built as a mausoleum for himself and his descendents (Birley 283). It is interesting to note that in all his travels, Hadrian paid respects to local gods by visiting principal shrines and restoring or building new shrines.

However, not all of his attempts at building were successful. In 130, Hadrian tried to rebuild the ruins of ransacked Jerusalem in his name. On the site of the Jewish Temple, he began building a temple to “Jupiter and the Emperor.” The revolt by the Jews in response to his desecration of their temple resulted in the only major war of Hadrian’s career that resulted in the murder of tens of thousands of Jews. Eventually Judaea was abolished and renamed Syria Palaestina and the hatred between Jews and non-Jews grew (Grabsky 165). However, since Christians were not included in the conflict and therefore were not excluded from Jerusalem, the city became overtaken by Christians. At the end of his travels, Hadrian retired to Tivoli, an one square mile estate that he populated with replicated copies of sights seen during his travels. His estate had approximately 300 acres of pleasure gardens, reception halls, baths, a library, guest quarters for his advisors to live in and a man-made island to serve as Hadrian’s private retreat (Brown 45). In preparation for his death and eventual succession, Hadrian adopted Lucius Commodus in the summer of 136, but when he unexpectedly died, Hadrian chose a senator Antoninus who already had the favor of the Senate. Soon after, Hadrian died leaving only his nephew Annius Verus, who would be known as Marcus Aurelius, to continue his legacy as the adopted son of Antoninus (Birley 290).

Of all of his achievements and buildings that displayed his adept skill for design, the Pantheon is the most impressive and well-known. Despite all of the fascination and admiration surrounding the Pantheon, surprisingly little is known about its true origins. Its architect is unknown, but the discovery of date stamping on bricks has led historians to determine that it was built between 118 and 128 CE in the Piazza della Rotonda in the Campus Martius area. In fact, the largest historical indicator of the architect and patron of the Pantheon, the inscription carved into the façade, is misleading. The ancient Latin inscription on the entablature on the exterior reads “M·AGRIPPA·L·F·COS·TERTIVM ·FECIT”, or “Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, three times consul, built this.” Although it is can be assumed that Agrippa, who was the lieutenant, advisor and son-in-law to emperor Augustus, was the architect and creator of the temple that now stands in Rome, this is an inaccurate assumption. Agrippa built the original Pantheon on the same site in 25 BCE as a temple dedicated to all of the Roman gods (“pan” meaning all and “theon” meaning god). However, this original structure was destroyed by fire and eventually the restored version erected by Domitian was struck by lightning and also burned beyond repair. These temples were replaced by the present structure that was built by the emperor Hadrian in approximately 125 CE. Although he clearly retained the large inscription on the exterior portico of the Pantheon, Hadrian left few traces of the original temple.

It is unclear why Hadrian would intentionally mislead visitors about the origins of the Pantheon. The Roman emperors were not known for their modesty, and it seems unlikely that Hadrian would have humbly deflected praise for his creation, especially when considering the grandeur and awe-inspiring design of the Pantheon. However, historians have speculated that there were both personal and political reasons for Hadrian’s inscription. Hadrian was a connoisseur of architecture and it is possible that he wanted to memorialize Agrippa, the man who oversaw the construction of many buildings in the Campus Martius area. In addition, Agrippa was associated with the deified emperor Augustus and therefore the inscription served as a public reminder of the connection between Hadrian and the late, beloved Augustus (Sullivan 60). The inscription is significant mainly because it is an unusual and bold declaration that cedes credit of a significant building to another person.

The Pantheon continues to be celebrated as an architectural wonder because of its innovative design that has been preserved even after 1,875 years of continuous use. The pagan temple survived the Middle Ages when Pope Boniface reconsecrated the Pantheon as a Christian church dedicated to martyred saints in the early 7th century. As a result, while decay and modernization have eradicated all of the other ancient buildings in the Campus Martius, the pantheon remains entirely intact with only its original decorations missing.